When Archives give no answers: Anna Atkins, Jamaica and the natural history of photography Zakiya McKenzie – March 2024

When archives give no answers, imagination turns evergreen evidence into depressing blues.

When archives give no answers, arresting colour is signal to possibilities of the past.

When archives give no answers, fact itself is ashamed to be in formal setting for having no scholarly reference of its own existence. No citation of its presence. For having no backlog of historic papers to point to it being true. When archives give no answers, it is left to inference, to learned deduction, to guess work to say that this happened.

——

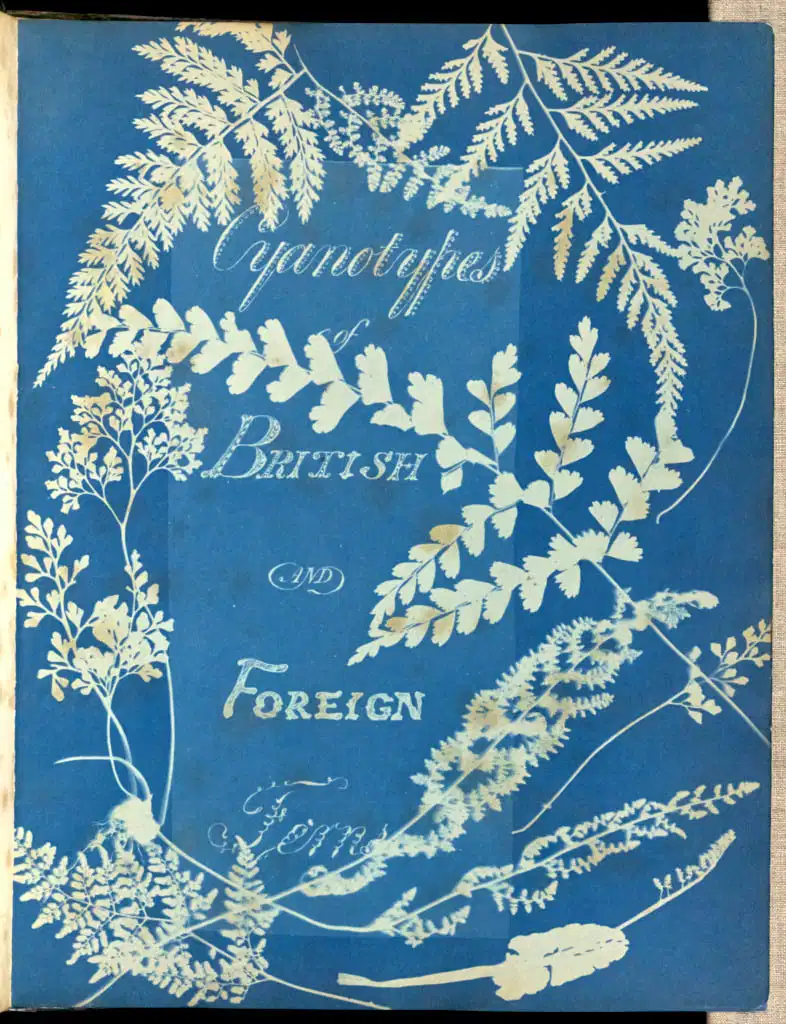

Anna Atkins’ cyanotype botany studies present a unique series of images that were on the cutting edge of technological advances in science and natural history. Atkins is also a pioneer of photography; her cyanotype photograms were among the world’s first books with photographs. Less mentioned is that plants from Jamaica, captured by Anna Atkins, are among these— the world’s first photographs. Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns (1853) and Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns (1854) distinctly included plants from the foreign island. How did Anna Atkins get her hand on Jamaican plants? Currently available scholarly work is yet to answer this question directly.

Anna Atkins opened the way for a novel understanding of plants. There is something bold revealed in the blueness of the images. They mesmerise as much as they muddle the reality of their own production. It is easy to forget how much of the advancements of modern science were made in slave economies and made because of slave economies. Born in 1799, Anna Atkins was in good position to learn about the cyanotype process at this early juncture in the development of photography as the daughter of Royal Society scientist, Sir John Children. Atkins was also most likely to have featured Jamaican plants so prominently in her work because of her proximity to slave plantations.

Anna Atkins’ husband, John Pelly Atkins, came from a slave-owning family. J & A Atkins, the investment company of his father and uncle, acquired two plots of land and 89 enslaved people from Robert Lauder at Hyndford plantation, St Vincent in 1799. The majority of Alderman John Atkins’ (Anna’s father-in-law) land estates were in the island of Jamaica. By 1820 the father and son were trading as John Atkins & Son. They were awarded for loss of income from a number of Jamaican plantations at the abolition of the British slave system in 1834. They received compensation for losing the forced labour of:

99 enslaved people at Trafalgar Plantation, Portland parish

99 enslaved people at Hopewell Plantation, Port Royal* parish

120 enslaved people at Mount Hybla Plantation, Port Royal parish

183 enslaved people at Dublin Castle Plantation, St Andrew parish

214 enslaved people at Hector River/Haining Plantation, St Thomas-In-The-East parish

220 enslaved people at Skibo Plantation, Portland parish**

There were at least six other claims submitted for plantations in Jamaica and one in Bermuda. When the elder John Atkins died in 1838, Anna Atkins’ husband inherited all of the properties in the colony of Jamaica.

This obvious Caribbean connection has been left out of nearly every study that contextualises Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes. Maybe because it fouls the story of the innovation. Maybe because it takes away from the glory of a woman breaking the glass ceiling in art and science. Maybe because slavery was just du jour. To say this flags up a lack of rigorous inquiry in past works on Atkins life and raises questions about who writes the archive, who interprets it and whose knowledge and experience is left out of the story. Anna Atkins work has been ‘resurrected’ and returned to the archive since the 1980s by academic research and institutional exhibitions. Through all this, there is little reflection on the metadata, on what the inclusion of Jamaican specimen in the cyanotypes of Anna Atkins tell us about the societies in which innovations were made in science and technology in recent history. As much as archives are the sum of the material repository held on a subject, archives are then just as much haunted by what they do not hold. By what they do not retain as a material representation of a reality to be remembered.

In acknowledging that there are likely things that happened outside of recorded history, we are left to wonder about Atkins’ interaction with the Black Jamaicans, wonder about what she thought of her husband’s business, wonder about who may have been there when she collected Jamaican ferns and flowering plants. Atkins own personal papers are not retained in any current archive collection; some scholars suggest that they have not survived, while others suggest that her scientific correspondences were made through her father, Sir John Children, and therefore, never existed.

Her inscriptions and introductions in the original copies of her volumes do exist. The only sure thing, supported by the archive, is that Atkins presented cyanotype images of Jamaican ferns and flowering plants.

——

When archives give no more answers, history ferments in old vats of time, ageing and dusting when mixed with our air (era).

What then of those events that have not been recorded or remembered as fact but are likely to have happened nonetheless? Where do these untold realities belong? What of history outside the collective and composite memories and myths of a shared past? If there is no archive of its existence, how do we begin exploration of ideas so taken out of their original context?

What is artful about production via necropolitics?

The intensity of the blues.

Ruined beneath the blues.

- The historic parish of Port Royal is now divided between Kingston and St Andrew parishes

**All numbers of the enslaved people in Jamaica were recorded in 1832, except for Mount Hybla, which was recorded in 1831.

References

‘Alderman John Atkins’, Legacies of British Slavery database, http://wwwdepts-live.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/22420

‘John Pelly Atkins’, Legacies of British Slavery database, http://wwwdepts-live.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/592811670

Fara, P. (2004) Sex, botany and empire: the story of Carl Linnaeus and Joseph Banks. Cambridge: Icon Books (Revolutions in science).

Musgrave, T. and Musgrave, W. (2000) An empire of plants: people and plants that changed the world. London : New York, NY: Cassell ; Distributed in the United States of America by Sterling Pub.

Schaaf, L.J. (2003) ‘Atkins [née Children], Anna’, in Schaaf, L. J., Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T004852.

Schaaf, L.J. (2004) Atkins [née Children], Anna (1799–1871), botanist and photographic artist. Oxford University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/37132.

Schiebinger, L. (2009) Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World. Harvard University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvk12qdh.

Leave a Reply